Case study one: Doing creative practice ethics in painting and video with other cultures

Name: Michal Glikson

Doing: PhD in Fine Art, School of Art ANU

Doing creative practice ethics in painting and video with other cultures

Michal Glikson is a PhD scholar at the Australian National University, and her study is an investigation of peripatetic art practice across cultures. The methodology of this practice involves moving and changing spaces and places, noticing subtle variations in environment and culture. It uses storytelling, portraying significant events and encounters with people, and through diarising the lived experience of peripatetic life.

This practice builds on a double degree at ANU, in Fine Arts majoring in painting and another degree majoring in Politics with Anthropology, with an Honours in Painting and a Master degree in painting at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda.

I remember one of my anthropology teachers’ viewing paintings I had made as an undergrad during an early trip to India and saying, “these are ethnographic paintings”. And I remember thinking wow. That’s where my connection between painting and the ethnographic began.

Project description:

I worked with a squatter family in Lahore and the practice became about revisitation and return. I had met this family prior to my project through background research in 2011. I’d started spending time with them, drawing them and filming them. They saw the kind of paintings I did, they were really keen to have their story told. I wrote into my proposal I would like to work with this family because they were dealing with homelessness, should I be able to reconnect with them. I didn’t know if I’d be able to find them again. When I went back to Pakistan in the second part of my project I was able to reconnect with them and they were still keen to work with me. So I spent a lot of time with them filming and sketching. In the exegesis I describe how their story became my story – in the paintings and in life as I could not keep visiting them without making some contribution to their life, as I could.

The project is yielding paintings and also about 30 films. The films were initially created for documentary purposes to illustrate conditions and processes of the field. Some of these films have evolved in function and now are also associated works in tandem with paintings. For example, where I’ve gained permission from subjects, I made small films about them, where I met them, and what they were doing. Post field work, I noticed how the films polarised with the paintings in that I’m working with miniatures and there’s a lot of refinement. I am recontextualising the subject from the rawness of the reality in which I met them to express what I felt about the human being, that is what miniature was traditionally used for – making legends, elevating subjects out of their ordinary context.

Ethics process experience:

The process of developing the ethics application took three to four months. It was begun in the first months of candidature to meet the requirements for engaging in human research. In the first instance Michal wanted to work with Indigenous peoples in Australia, as well as in India and Pakistan.

I’m not conducting formal interviews… My aim was to allow the material to come to me – rather than ‘hunt’ it out. So in this way I had to try and predict who I might encounter my journeys and excursions (the forms that movement as my methodology took). This was difficult because journeys are innately uncertain – all kinds of opportunities and invitations crop up (and this makes it a stimulating method). It helped that I was clear why I wanted to work across cultures. I wanted to story human experience – others and my own.

I do remember that I began to write – wanting to gain clearance – and the menus on the forms online started opening and opening, and I began panicking, thinking I will never complete this ethical program, and that my work will be delayed and delayed. It seemed a minefield, and I would have to go all the way through it without even knowing if I might ever connect with an indigenous person. Perhaps I could have done this part retrospectively – and applied for clearance post field – and the thought of having to go into all of this again, and perhaps again, and perhaps be told post field that work I had made had contravened the ethical [position of the University]- this appalled me. It was sad. I had to let go of the possibility of storying indigenous experiences because it would have meant incredible work. A whole other PhD. I decided the project couldn’t contain it. Ultimately it meant that I didn’t take steps to spend time with Indigenous families or communities. I guess I could have coincidently run into someone with Indigenous heritage. I guess I could have applied for retrospective ethical clearance. But then I would have had to put in another ethics application – as I understand. So I held back, I curtailed my impulses essentially – I didn’t travel to certain localities etc.

[Ethics process are] incredibly important. Saying that though, you know, if I had framed my research question knowing that I’d have to go through this ethical process, I don’t think I could have. I came to the PhD too ignorant. I didn’t even know that I’d have to go through this depth of ethical clearance. This was a way I’d been working for a long time and suddenly it was a minefield. It was quite confusing – in desperate moments I did wonder to myself why I had been encouraged to do this research – weren’t people concerned about what I was doing? Maybe because I was working with something like miniature painting this stole attention from the social dimensions of the practice. I can see why researchers stay in their studio and work with the abstract. I think I have more in common with artists in mediums such as dance or photography – and maybe I should have investigated their ethical process for my own understanding.

Project issues:

Some of the issues Michal encountered in peripatetic art practice fieldwork in India and Pakistan included:

Cross cultural research collaboration; consent (given on film, across cultures and different languages); working with children who may be employed; people from marginalised communities and fieldwork in a caste culture; projecting/ speculating on a “participant identity” for the ethics committee; different discipline approaches to ethics; and creative practice research, inside and outside the university:

So the ethical challenges presented through the variety of potential subjects in that these might be children, people from marginalised communities, they might be vulnerable in different ways, and probably would be because that’s the territory where I felt the more important stories lay. I had to do a large amount of projection about my subjects, and tailor my ethical approach to working with vulnerable individuals/groups and this cut my work out for me. My ethics application was inches thick. I could only have completed it because the study developed on work I’d been doing across cultures for a number of years, and thus I had understanding of these and was able to project.

The research integrity that I carry into my study isolates me as an artist. I cut myself out from being able to collaborate with many people within India and Pakistan by being governed by a different set of ethics than they are as artists. How can I work with artists who walk up to a homeless family and start photographing without even asking? I’m already isolated through the paintings because I work with miniature in a maverick way, and am not part of contemporary miniature coming out of Pakistan, even though I trained there. So the ethical paradigm isolates me further. So if I give a workshop at the National College of Arts, I’m not asked to do a workshop in the miniature department, I’m asked to give a workshop in life drawing, I’m asked to take students out on the street. And doing so I have to impart to them the same code of ethics that I embody which makes me an anomaly as an artist and teacher.

I had 16 months of fieldwork, I could go really slowly and learn about my ethical approach organically. A lot of the people that I’ve worked with, if you walk up to them with a piece of paper and you say can I film you, they’re just going to be very frightened. If you have the time to spend time with them, come and have tea with them every day and then you know after a month, you start drawing and then filming, you can do it that way. As I saw it, permission unfolded. I ended up using film as a way to evidence peoples’ permission because after a while film was the best way to record their willingness to work with me. A celluloid consent form. When people try to do projects in short amounts of time then I think it is more challenging to work ethically but working with people over time can hold a more real kind of consent.

Michal also worked with children, and working children in vulnerable circumstances:

I had to say OK I’m working with working children. I had to actually write – “in some cultures children are working children”, and then I had to describe how I planned to engage with working children, which was essentially to say that I would not disturb them. I had to describe what I do if children around me get hurt? What scenarios could happen? How would I behave? I had to really go into the nitty gritty of band aids and taking them to hospital. Where would I take them? You know what kind of bandage would I get if they fell over? What would I carry with me in terms of a first aid kit you know?

In conclusion:

One of the problems is there’s some examples of practice out there but not many set up to show how it was done.

You know some things you have to feel incredibly strongly about something about because the research integrity process is huge. I don’t regret doing it and I’m not saying it’s not important, but it is huge. It tested my commitment. I realised the scope of what I was attempting. It was good to think about what I was attempting, but it would have been much easier if I had been prepared. If somebody had mentioned to me when was thinking of applying to the PhD program that what I wanted to do was going to involve huge ethics application. I could have (and would have) begun my research with that before even starting my candidature… I had no idea that what I had been doing, what I wanted to explore more formally – storytelling – would have that degree of ethical edginess.

More about Michal

Website: http://www.michalglikson.com

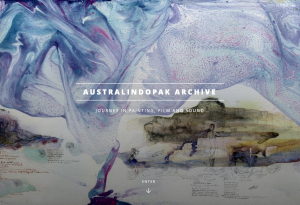

The website has an interactive virtual tour of the paintings and films generated by Michal’s Phd research. The Australindopak Archive has been developed using a virtual tour software, and brings together digitised scrolls, observational films, and sound compositions. These works comprise a major part of the research project Towards a Peripatetic Practice, and were developed from sketches, footage and sound gathered while traveling.

Thesis link: When available

Michal Glikson was interviewed by Megan McPherson via Skype in April 2016.

** Australia Council: Children in art protocols

** Consent from National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated May 2015). The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra